The rise of 3D printing technology has opened up exciting new opportunities and possibilities for medicine, particularly in the medical device space. Some early game changing instances have already been reported this year, as a 3-D printed medical device was used earlier this year to save an infant’s life.

In late May, 6-month-old Kaiba Gionfriddo was diagnosed with tracheobroncholomalacia, a condition where breathing is impaired due to soft cartilage throughout the trachea. Had Kaiba been brought into Univeristy of Michigan’s C.S. Mott Children’s hospital a year later, this condition would have been fatal. Fortunately for Kaiba, among those handling his case was Scott Hollister, a biomedical engineer who had been exploring the medical applications of 3-D printing. When no option seemed available, he stepped in with the idea of creating a custom splint that would fit into the infant’s trachea. The medical team proceeded to take a CT scan of Kaiba’s chest and then create a 3-D render of the child’s trachea. From here, they designed and printed a custom splint that would be a perfect fit once implanted. Within three weeks, Kaiba had resumed normal breathing without the assistance of a ventilator.

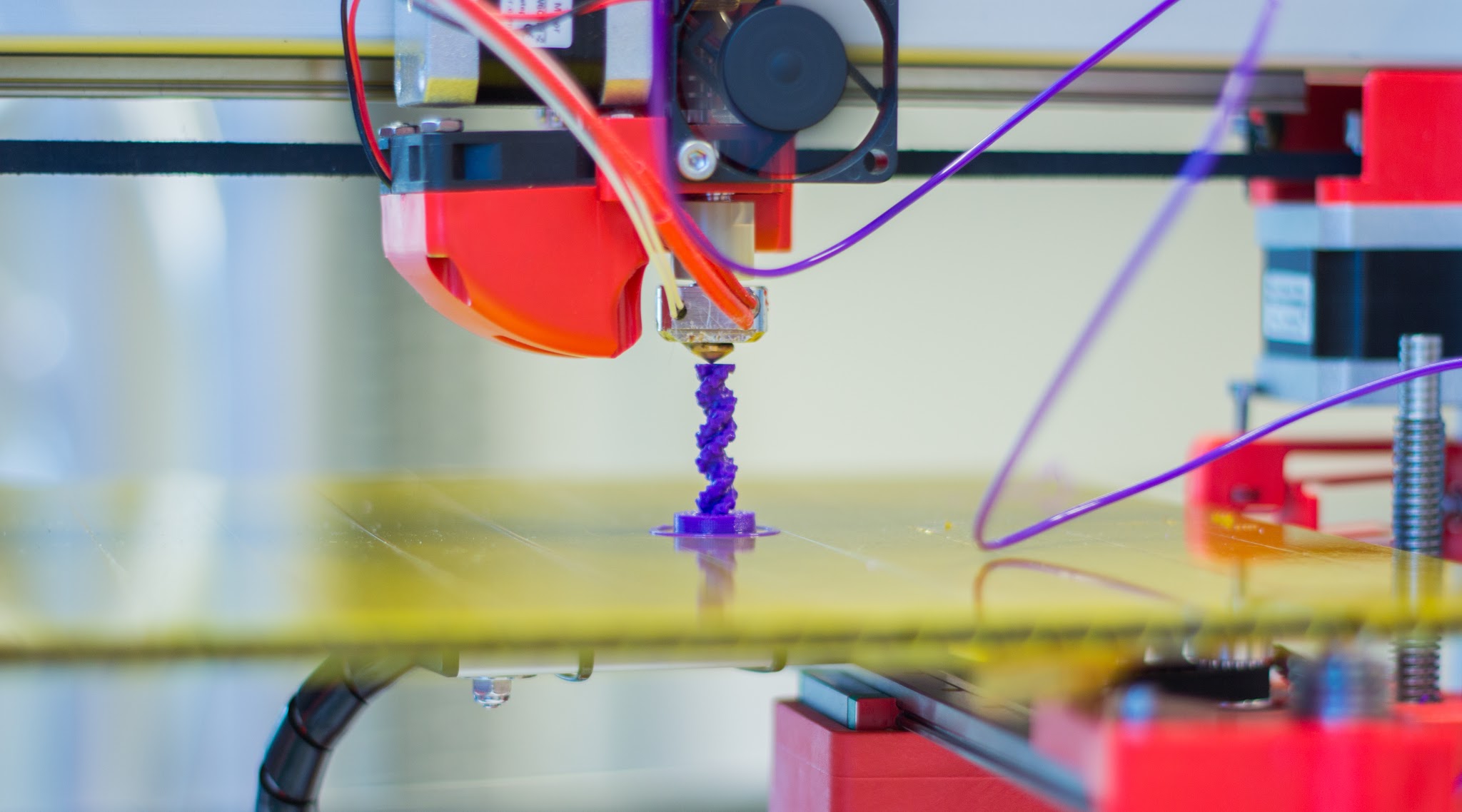

The case is an early example of what could soon become the norm in life-saving medical technologies. While the technology of 3D printing has been around since 1984, the last five years have expanded the range of models expanding both the large scale capabilities and reach in larger consumer markets. The trend in technological development shows that as 3D printers are becoming smaller and cheaper to make, their range of capabilities are growing in depth. For hospitals and medical centers, this means owning a 3D printer could soon be common practice and no longer a privilege afforded to specialized centers such as C.S. Mott’s Children hospital.

Combined with CT Scanning capabilities, 3D printing could lead to an increased number of devices that will be created to specifically match the need of that patient. Additionally, as the range of materials that can be printed are expanded, common and frequently used disposables could soon become printed based on need, potentially freeing up shelf space and opening up inventory for items that previously could not be justified keeping on site.

Assuming the inevitability of 3D Printing devices in hospitals, it is worth predicting how this new technology could affect companies that currently manufacture the devices that could be printing. First, how medical devices are licensed and intellectually owned could be brought up into debate. As hospitals begin printing their own devices on a larger scale, manufacturers of those designs might claim licensing over their design. While the hospital would seek to save costs by printing such devices themselves, these manufacturers could charge a licensing fee as is seen in other industries. Claiming licensing over 3D printing blueprints for certain medical devices could offer manufacturers a unique financial incentive as well, potentially allowing them to evade the medical device tax posed by Obamacare. One way to think about how this system could function is to consider how we digitally purchase music today from a platform such as iTunes. While we are not paying for a physical manifestation of a song, we still pay a licensing fee to iTunes as part of every music purchase that grants us rights to play that song. Device manufacturers could lease product blue prints to hospitals the same way, charging hospitals for the rights to print certain materials.

As has been the case with the music industry, 3D printing could also lead to “pirating” medical devices. This issue has already arisen in other fields of 3D printing. In May of this year, a US company Defense Distributed produced a blueprint that could be downloaded and used to print a working firearm, spurring a new debate over gun control amid fears of unregulated gun printing. With a life on the line, it is not unreasonable to imagine a scenario where a hospital on a tight budget could turn to a pirated blueprint for an emergency device. Unfortunately, these unlicensed blueprints would have not have the same guarantees and would put a patient at risk.

Considering again the manufacturers of medical devices, one final problem 3D printing could pose is the lost of income medical device manufacturers could face as a their products become increasingly printed instead of bought in bulk. While it is easy to chalk this up to pure capitalism and claim it as an instance of new technology replacing the old, it cannot be ignored that the profits of these sales are more often used to fuel the innovation and creation of new technologies. With the sudden loss of a stable revenue stream, manufacturers could curtail researching efforts, resulting in a wide spread reduction in the rate at which new medical devices are produced.